THE ELECTRONIC CONTROL UNIT

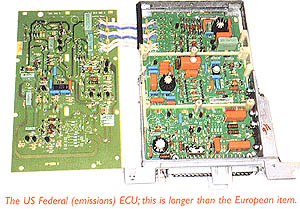

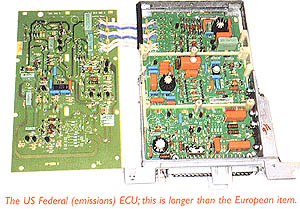

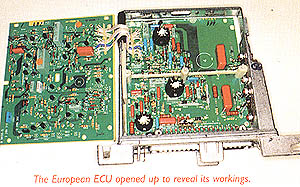

The L Jetronic ECU (classed as 5CU by Lucas) for European cars is about

half the size of that for the old D Jetronic (Lucas 3CU) used on the V12

and was notable for having a much better quality connector with 35 pins.

The main input signals (see wiring diagram) are engine speed (at pin 1,

derived from ignition pulses), airflow as a voltage input from the airflow

meter, and coolant temperature. US emission ECUs are about 3 inches longer

to accommodate the extra circuitry needed to deal with the Lambda signals

(see photos). The less significant trim factors applied are air temperature

correction, full throttle enrichment, idle enrichment (emission cars only)

and cranking trim instigated from the starter relay. An idle fuel trim

screw is provided at the airflow meter so there is no need for the ECU to

be provided with any means of adjustment.

ECU OPERATION

The L Jetronic control unit used analogue technology like its predecessor D

Jetronic but at least moved on from having many discrete transistors to

using integrated circuit devices composed of many transistors connected to

perform specific tasks. The 3 integrated circuits are housed in round metal

cases with a clumsy arrangement of 12 or 14 connection wires radiating

spider fashion from the underside quite unlike the neat dual in line

devices which are now almost universal (see photo). The ECU operating

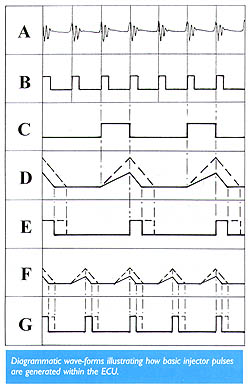

principle was fundamentally based on a counter and several timer circuits

responding directly to voltage inputs from the various sensors to generate

pulses following simple laws to govern the injector opening periods (see

diagram showing wave-forms).

The ignition signal is taken from the coil negative terminal and because

voltage spikes as high as 400 volts can be seen at this point the input

circuit attenuates the signal to a safe level (A) and creates a trigger

pulse (B) from each ignition cycle. This is then applied to a frequency

divider which produces one pulse for each engine revolution, at every third

ignition spark (C) on an 6 cylinder engine like the XK 4.2.

|

The way Bosch describe the generation of the basic injector pulse is

suggestive of an interesting circuit configuration which is widely used

whenever pulses need to be varied in constant proportion with frequency.

Another common application is in the advancing timing light found in almost

every garage workshop, where the set number of degrees remains the same

regardless of engine speed.

A rising edge at the frequency divider output pulse permits a capacitor to

charge from a constant current source to create a linear rising voltage

ramp (D). The next falling edge from the divider pulse reverses the action

and starts the capacitor discharging linearly at a constant current to

create a downward voltage ramp. The basic injector pulse is created during

the period of the downward ramp (E).

Now the clever bit about this is that as the engine speed rises so the time

available for the upward ramp becomes shorter so the discharge period takes

place from a lower voltage and is itself proportionately shorter (F). If the

engine speed is doubled but the airflow remains

the same then each cylinder will draw half the amount of air, the charging

slope angle will remain the same but will be for half the time therefore

the discharge slope will commence from half the height of before, thus the

basic injector pulse will be halved (G) and the total amount of fuel

injected will remain matched to the total amount of air inhaled. Note that

the charging current and therefore the slope of the first ramp is

controlled by the airflow meter, a higher flow condition being shown

dotted, whilst the discharge current and the downward slope of the second

ramp are always constant. By this relatively simple circuit configuration

the basic injector pulse is inherently corrected according to any changes

of speed and airflow.

Actually it is quite impossible to verify that all this really happens. The

basic pulse is real enough and it does vary as described but the business

with ramps up and down can't be seen by poking around the ECU with an

oscilloscope, so perhaps we have to regard it all as a notional explanation

rather than an exact one, although it certainly is consistent with how the

ECU behaves. To compound the mystery an explanatory document issued within

Jaguar Experimental Department in 1978 to introduce L Jetronic stated, and

I quote verbatim, "the fueling information is carried in a memory so that

for any combination of intake airflow and engine speed the memory gives out

a signal which is proportional to the amount of fuel required". In fact, L

Jetronic does not use memory technology at all but maybe this illustrates

how unfamiliar engineers were with electronic systems at that time and so

such an explanation was thought to be adequate. Just because something is

in print doesn't mean it is necessarily accurate!

Having generated the basic injector pulse it is then passed through a

multiplier stage and the various corrections for coolant and air

temperature, battery voltage, full load enrichment, cranking and

after-start enrichment are applied. Of course, unlike modern digital

systems which scan the various inputs and convert their signals into hex

code for manipulation according to a program, in early systems like L

Jetronic the voltage signals from the various sensors directly influence

timer circuits to produce the final injector pulses. We have just seen how

this happens with the airflow meter signal in the creation of the basic

pulse and the others have a similar effect during the multiplier stage.

|